Hermann Ebbinghaus

Why do we forget the things we have “learned”? Are all memories equally forgettable? How can we improve the quality of the memories we create?

‘if nothing in the long-term memory has been altered, nothing has been learned’ ~ Sweller et al (2011)

We could argue all day over what constitutes learning but I think the vast majority of teachers would have ‘remembering’ somewhere in their own preferred definition. We want our students to remember the things we teach them so they can recall them or put them to some use in the future. The problem is that sometimes it feels as though there is a memory vacuum positioned above the door, sucking the learning out of students as they leave so that when they return the next lesson they can recall little of what they learned. That’s not actually very far from the truth.

In 1885, Hermann Ebbinghaus’ published his study into Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology where he conducted a series of experiments to try to determine the rate at which we forget things, the factors that influence the quality of a memory and how we can improve our ability to recall what we have learned. (See HERE and HERE for some great summaries of his findings.)

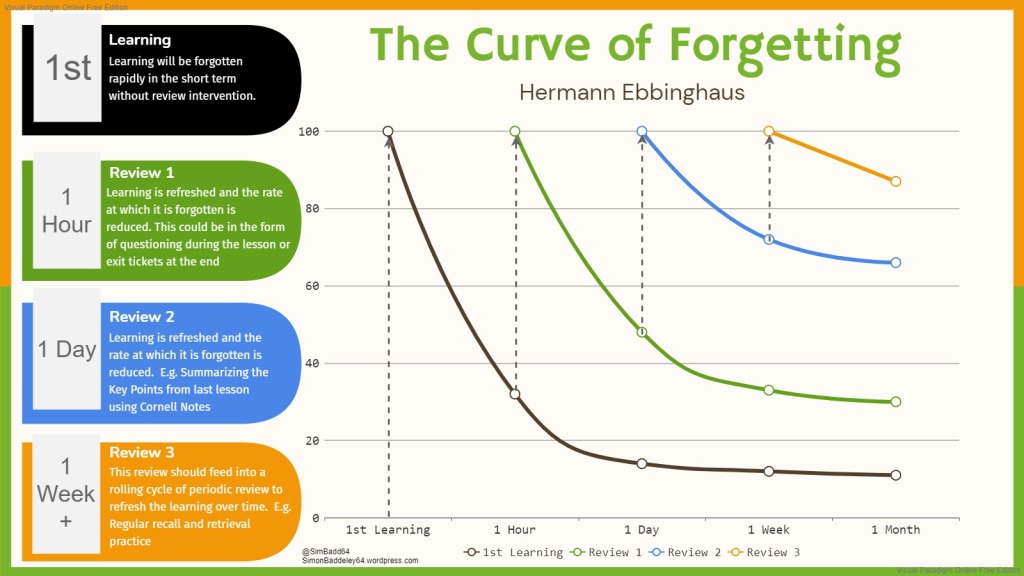

Ebbinghaus discovered that new content is forgotten very rapidly over the first 24 hours after learning but the rate of loss gradually slows over time. The graphical representations of this data that I have found all start to measure the loss at 100% of what was learned. What was learned and what was delivered are two very different entities and Ebbinghaus acknowledges this. He categorised the factors affecting the quality of initial learning as being:

- How meaningful we perceive the information to be

- The way it is presented us

- The physiological actors (stress, sleep, hunger etc) that may be distracting our thoughts.

Making the Information Meaningful

This is usually presented as making real world links or stressing the importance of a particular topic these days. The perception of importance is a very personal thing. It will drive some people to learn reams of statistics for their sports team while they neglect learning times tables and will result in hours of patient practice to learn the latest TikTok dance routine whilst struggling to focus for more than a few minutes on a writing task.

Our ability to influence what someone else perceives as important when it comes to learning is limited. Our students just don’t find tiling the bathroom of an alien as important as we would like to think they do when we sugar coat a task. What we can do however is create the ethos that learning itself is important on a whole school level and underpin it with systems and expectations that support all learners in accessing learning in a meaningful way.

Presenting the Information

This has been interpreted in as many different ways as there are articles about the ‘Forgetting Curve’. One popular inference here is that the delivery method must be engaging for the new learning to be memorable. The more we learn about cognitive load theory, however, the more this interpretation loses credibility. Is the student thinking more about the task or about the content?

The mantra I have come to accept at the core of my planning is “If students aren’t thinking about it, they aren’t learning it”. The tasks I plan have the content at their core and as little extra cognitive load as possible. I reuse task layouts regularly so students become familiar with the process involved which means they are dedicating less working memory to it and therefore more able to focus on the content. Most importantly, if the task is more memorable than the content, the content will be forgotten quicker because it will never have been learned fully in the first place.

Physiological Actors and Distractors

I would suggest that people remember important events more easily because they are “presented” in a way that consumes more of the person’s thoughts at the time. If you were to witness a major event like the attack on the Twin Towers or the assassination of President Kennedy, chances are it would consume quite a lot of your thoughts at the time. The hunger pangs because you missed breakfast or that wasp buzzing around nearby would have less of an impact on the quality of your thought about the event and therefore your memory of it would be stronger.

Obviously, attempting to make a lesson a “major event” in an attempt to make the content more memorable is missing the point. It is the quality of thought that influences the starting quality of the memory not the strength of the experience. How much distraction is there in the room? How distracting is the task itself? How much thought is the student diverting from the content to something else?

Diminishing start points

The forgetting curves I have seen all represent memories as starting at 100% and dropping away on a curve over time. It is important to remember that the curve of forgetting represents 100% as being everything that was learned. This is distinctly different from everything that was taught. Every distraction from learning about the content would result in a lower than “100% of what was taught” starting point.

Let’s say we taught 10 spellings during a lesson and tested students a week later to see what they remembered. If the curve was applied to make predictions about the results we might predict that every student would remember about 4 spellings accurately. In the classroom however there are wild variations from this prediction with some students remembering very few and others getting all of them correct.

Ebbinghaus accounted for these in a number of ways but firstly by theorising that certain physiological actors impacted on the quality of the memory. If, for example, a student was under stress to perform well or distracted by hunger, they might form less secure memories of the content being learned and therefore forget things more rapidly. Distraction of any kind diminishes the quality of our thought on a topic. As Paul Kirschner and Pedro de Bruyckere theorised (explained brilliantly in this blog by David Didau) humans can’t multi task; they simply switch from thinking fully about one thing to thinking fully about another. It follows then that when there is a distraction in the classroom the distracted student must also be switching their thinking from the content to the distraction.

So let’s return to our 10 spellings analogy. If a student is distracted whilst being taught 4 of the spellings the quality of their thinking about them will be diminished and they will be forgotten quicker. In this case, the 100% start point on the forgetting curve is already 40% below all of what was taught. That goes some way to explaining why our students sometimes return with blank faces the following lesson.

What can we do to aid memory?

As I have said above, the initial quality of thought during learning is the most important factor in creating memories. To aid memory most, improve the quality of the thought students exert on the content they are learning.

The biggest take away from Ebbinghaus’ research was however that memories can be strengthened by revisiting them. If we revisit something we have learned within a short time frame (under 24 hours as a maximum) then two things happen.

- “What has been learned” gets topped back up to a 100% starting point

- The rate that the information is forgotten decreases

Ebbinghaus found that recalling information from memory at increasingly spaced intervals was the best way to strengthen the memory and counter the curve of forgetting. Each time we recall something we effectively “top up” what has been forgotten since first learning it and also slow the rate at which it is forgotten. Because we are now likely to forget it at a slower rate, we can leave the retrieval a little longer. As a rough guide it is useful to remember what I’m calling the One Rule: Have students recall information within one hour then one day, one week and one month of it being first taught.

1 Hour – First Review

At some point, probably towards the end of the lesson, it is a good idea for students to recap and review any new content you have covered that lesson. This action of revisiting it within an hour is the first step in slowing the rate that students will forget that new content. This could be as simple as a quick fire round of questioning answered on whiteboards or an exit ticket exercise.

1 Day – Second Review

A quick review built into the next lesson in some form will again refresh the knowledge but more importantly slow the rate of forgetting significantly. If you make a habit of using recall activities as your “Do Now” task to start the lesson, it is a good idea to reserve half of the activity for content covered in the previous lesson

1 Week(+) – Review 3 – Ongoing Periodic Review

If you reserve half of each recall activity for content covered in the previous lesson then the other half should be populated by a rolling cycle of content drawn from previous weeks and months. The rate of forgetting will have slowed significantly by this point but students will still forget unless they revisit topics over time.

It is important to state an obvious thing here. Make sure any errors in what students recall are corrected immediately. It is surprising how quickly a memory can become warped over time unless efforts are made to correct it.

The Bottom Line

- The quality of thought and how much the new content consumes that thought is of paramount importance. When planning a task I try to keep asking myself “What are students thinking about?” at each step.

- Introduce new information slowly and in small chunks. The reason a student can never get more than 5/10 in that spelling test might just be that 10 spellings is overwhelming and too much to remember at once.

- Make learning meaningful. Not just the learning in that lesson but learning itself. Learning should be the core of every school. Make no excuses and expect nothing less than the best. We can’t make our content memorable by turning every lesson into a major event but we can make learning itself and the pursuit of knowledge meaningful in itself.

- Review and recall new content quickly and soon after it has been first introduced. The majority of forgetting happens in the first 24 hours so it is a good idea to build new content reviews into the lesson itself. This could be as simple as a closed book Cold Call session of questioning or a simple exit ticket task.

- Embed the review process over time so that content is returned to periodically and constantly refreshed. The rate of forgetting slows each time but never disappears so keep the process going right up to the last opportunity before terminal assessments.

[…] The Curve of Forgetting […]

LikeLike

[…] to be recalled every month or so to keep it stable. With that said, following the Ebbinghaus curve, some educators suggest rehearsing 1 hour, 1 day, 1 week, and 1 month after learning something […]

LikeLike